SpaceX’s Starlink and T-Mobile have teamed up with an ambitious promise: to erase cellular dead zones from the map.

Meet the Experts

- Jeff Gwinnell is a connectivity specialist at TravlFi

- Nathan Popp is the director of operations at TravlFi

- Jeff Kagan is a wireless industry analyst and tech columnist

- Ferhan Nasim is the CEO of HubexTech

You don’t realize how much you rely on your phone—until it stops working. In the blank spaces of the map, where cell service gives up, T-Mobile and Starlink say they’re building a new kind of safety net: one that hovers in orbit and speaks directly to your phone.

If they pull it off, it could change everything about how we travel, recreate, and stay safe in the most remote corners of the world.

But as someone who’s spent more time than most bouncing between places where my phone’s only function is to remind me that it’s useless without a cell or WiFi network, I had questions.

How usable is this technology? Who gets access, and how much will it cost? Will it replace legacy emergency communication solutions like satellite messengers? And is it actually going to help people who live and breathe the off-grid lifestyle?

The answers, at least right now, are more complicated than all the positive press around the Starlink-x-T-Mobile partnership let on. Here’s an in-depth look at direct-to-cell technology and its implications.

The Promise: Your Phone Will Soon Work Anywhere

It’s a big promise, and a buzzy one. And steps have been set in motion to make it happen (eventually). It doesn’t start with the Starlink/T-Mobile partnership, though: In fact, Apple was the first telecom company to integrate satellite communication with modern smartphones.

In 2022, Apple launched its Emergency SOS via satellite partner Globalstar—a feature that, while limited to sending pre-scripted messages in life-threatening situations, made waves. Since then, the buzz has only grown louder.

T-Mobile and Starlink made a splash with their “Coverage Above and Beyond” initiative, promising a direct-to-cell (D2C) satellite connection launching in 2025. In 2022, the brands said there’d be “No extra equipment to buy. It just works.”

And in 2024, SpaceX launched the first direct-to-cell satellites, though the beta program didn’t roll out until early 2025.

Meanwhile, AT&T and AST SpaceMobile are in on it too, conducting test calls from satellites to everyday smartphones. Suddenly, the dream of a phone that “just works” wherever you are isn’t a dream anymore.

But here’s the catch: So far, for regular consumers like you and me, it’s limited to SMS text messaging. And “coverage” doesn’t mean what you think it means.

The Reality Check: Tech In Its Infancy

Behind the curtain, the tech is still in its toddler phase.

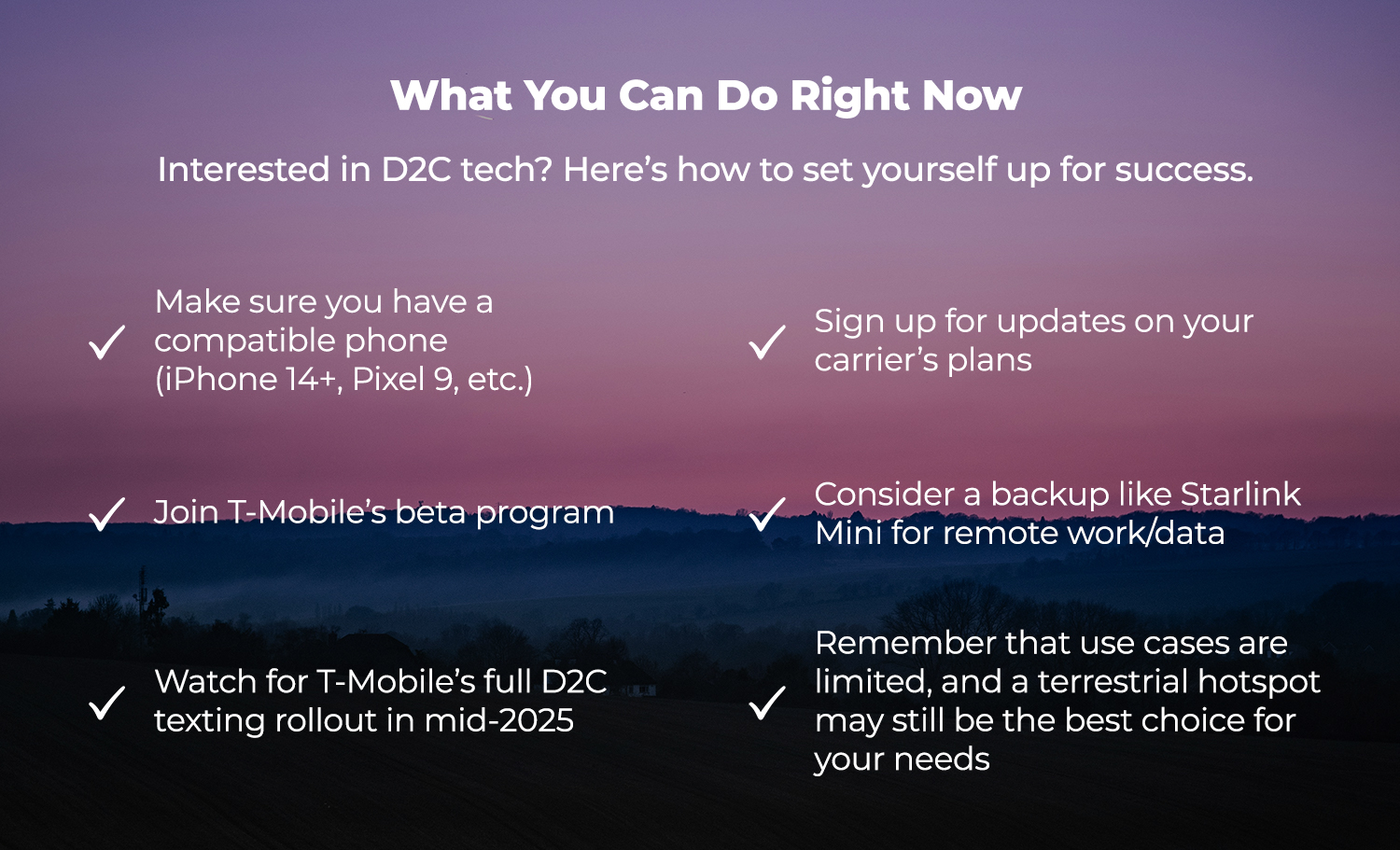

As of spring 2025, Starlink’s direct-to-cell service is still in beta, with commercial launch (for texting only) planned for July. Analysts say voice and data could follow in 2026 or beyond, but nobody’s putting money on exact dates.

For one, there’s the question of capacity. Out of the 7,100+ satellites Starlink has in orbit, the constellation of D2C-capable satellites consists of just a few hundred. That’s not nearly enough to serve millions of smartphone users, let alone keep up with our demand for TikTok, topographic maps, and turn-by-turn GPS in the middle of nowhere.

Additionally, it’s important to keep expectations grounded as far as how well the service actually works, says Nathan Popp, director of operations at TravlFi. “The actual model is more nuanced than most people think,” he points out. “Your phone will only be able to ping a satellite when one passes overhead, and only if your device is compatible, your view of the sky is unobstructed, and the satellite isn’t busy helping someone else.”

Ali Carr, co-founder of Basecamp, a community for outdoor professionals, said, “We camped in Joshua Tree for three days, two nights with no traditional cell service. Some of the folks had satellite access with their phones, and it worked—some of the time.”

“Mostly, it ate their batteries while it was searching for the satellites if they forgot to turn it off,” she noted.

All that said, it’s clear that this technology is rapidly advancing, and it seems like everyone’s game: The U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has given SpaceX permission to launch up to 7,500 D2C-capable for its partnership with T-Mobile.

On top of that, SpaceX is working with telecommunications companies from several countries, including Canada, Peru, Chile, and Switzerland, to create supplemental satellite networks globally.

Satellite Direct-to-Cell Service: How This Changes Everything

Traditional Cellular Internet

Traditional cellular networks rely on a dense web of ground-based towers, each with a limited coverage radius, providing what’s known as “terrestrial coverage.” Such coverage has evolved from 2G to 3G to LTE and now to the super-speedy 5G we enjoy today.

These networks (usually) deliver low-latency, high-speed connections ideal for urban and suburban environments. However, their reach is inherently limited by geography and infrastructure costs. And anyone who has traveled off the beaten path knows that there are plenty—more than plenty—of areas where ground-based cellular coverage does not exist.

Traditional Satellite Internet

Satellite internet, conversely, offers broader coverage but this has historically been at the expense of speed. Traditional satellite internet has long served as a lifeline for remote areas, like ultra-rural communities.

These systems typically rely on geostationary satellites positioned approximately 22,000 miles above Earth, introducing issues with lagging and necessitating specialized equipment like satellite dishes and modems. While effective in certain scenarios, these setups are often costly and cumbersome for everyday users.

Modern Satellite Internet

Even modern satellite internet services, like Starlink, require specialized hardware. It’s not typically something the average person with access to terrestrial networks is willing to invest in, even if they sometimes venture to remote areas.

A Joining of Forces

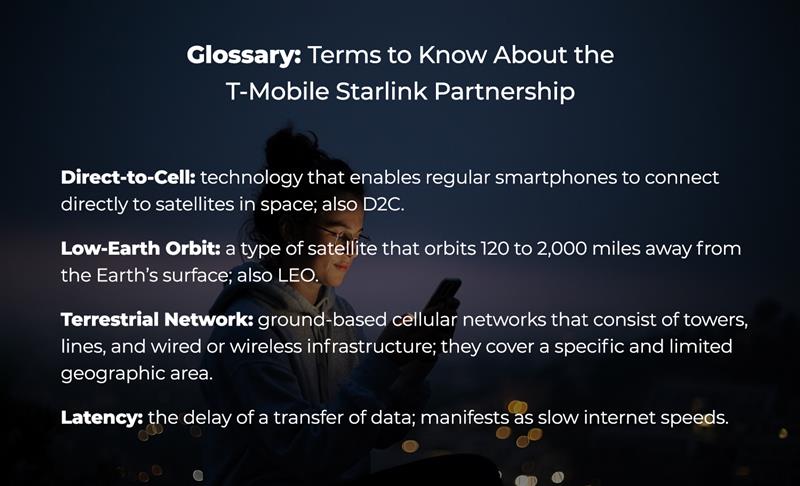

The convergence of these technologies through D2C aims to harness the strengths of both, mitigating their individual shortcomings. Now, instead of satellite data needing to bounce from your dish to wired data centers and back to your dish, the satellite talks directly to your phone. This effectively eliminates the need for infrastructure on the ground.

Plus, D2C technology utilizes low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellites, which significantly minimizes latency issues. Instead of signals traveling more than 20,000 miles from Earth, signals need only travel 120 to 2,000 miles.

This shift isn’t just cool; it’s transformative. For people living in rural communities, adventurers exploring the backcountry, and people in disaster-struck regions without functioning networks, it could be the difference between isolation and connection.

But with current satellite coverage and capacity, it’s not ready to replace terrestrial networks.

“Due to physics, economics, and network design, direct-to-cell is poised to complement, not replace, terrestrial cellular networks,” says Ferhan Nasim, CEO of HubexTech.

And in some places, that may never be the case, simply because there is no need. “High-density urban areas are best served by ground infrastructure, while satellite direct-to-cell fills rural and emergency coverage gaps,” Nasim explains.

The Fine Print: Latency, Compatibility, and Carrier Catch-22s

If you’re an outdoor athlete, emergency responder, boater, overlander, or someone who lives in a cell service dead zone, this is all good news. But it’s not quite right now news.

Today, if you need reliable connectivity in remote areas, your best bet is still traditional satellite internet or Starlink. And in urban and suburban areas, D2C doesn’t feel necessary in the absence of natural disasters or complete blackouts.

Down the road? It’s entirely possible that smartphones will become hybrid devices that seamlessly switch between terrestrial and satellite networks, and you’ll never know the difference. That’s the dream, and it’s getting closer.

But don’t cancel your current RV internet service just yet. The industry still has a long way to go before this dream is reality.

Usability Limitations

The most significant battle D2C customers will face on a daily basis is usability in the face of obstructions. For your phone to connect to the nearest satellite, you must have an unobstructed, clear view of the sky.

This poses a real problem in backcountry scenarios, such as when hiking in the bottom of the Grand Canyon or through a dense forest in the Pacific Northwest. In urban environments, should the service be necessary in the event of a disaster, high-rise buildings pose the same issue.

Carrier and Device Compatibility

Even when the commercial service officially launches (i.e., is out of beta) in mid-2025, only certain phones will be compatible. As of this writing, compatible phones include iPhones 14 or later, Google Pixel 9, certain Galaxy models, Motorola phones from 2024 or later, and the Revvl 7. If you have an older phone, you might be out of luck. Your phone also needs to be updated to the latest software edition to work with D2C satellites.

Technical Hurdles

According to Nasim, current limitations include low bandwidth—often only sufficient for SMS or basic data—latency challenges, limited spectral efficiency, and spectrum regulation complexity.

To achieve widespread adoption, Nasim says, breakthroughs are needed in several areas, including satellite capacity, bandwidth allocation, beamforming, and signal modulation.

Regulatory Roadblocks

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has approved the Starlink-T-Mobile partnership, but not without stipulations. Concerns about potential interference with existing services led to conditions aimed at protecting terrestrial wireless operations.

Moreover, current FCC rules classify Starlink's service as "Supplemental Coverage from Space," meaning Starlink can only act as infrastructure for carriers like T-Mobile, not as a standalone mobile provider.

Infrastructure Concerns

Adding more satellites raises concerns about orbital congestion and space debris, says Popp, raising the risk of collisions and interference with other networks. This is an area under close regulatory and scientific scrutiny.

Additionally, most LEO satellites have an operational life of about five years. Maintaining and growing these constellations requires ongoing investment and frequent launches. Regulatory bodies like the FCC and international organizations are grappling with establishing guidelines to ensure sustainable growth in this sector.

Implications for the Mobile Workforce

For digital nomads and remote workers, the implications are profound, even if they’re not near-term. The ability to maintain connectivity in remote areas could redefine the boundaries of the mobile office even more than they have already morphed in the last half-decade.

"In the near future, direct-to-cell will provide life-changing connectivity for digital nomads and remote workers, making communication possible even in the most isolated areas," Nasim predicts. “While initial services may focus on text and emergency signals, gradual improvements will bring low-bandwidth data capabilities.”

Jeff Kagan, a veteran wireless industry analyst, echoes this sentiment. "The satellite sector will continue to grow and offer more," he says. “It’s early days right now, but I believe the demand will be incredibly high going forward.”

Satellite-as-a-Hotspot?

Digital nomads who dream of beaming their phone to space and achieving work-worthy internet connections will be disappointed by the current status of the service. According to TravlFi connectivity specialist Jeff Gwinnell, it’s hard to say whether D2C could replace or bolster cellular hotspot services.

“As direct-to-cell is offered as text only at the moment, there’s only speculation with regards to how well the internet might work,” he says. “There may or may not be any restriction using the direct-to-cell service with your phone in hotspot mode in the carrier’s data plan.”

And even then, he says, the carriers might restrict how you use it. Think: no data tethering, reduced message speed, or limited monthly access buried in the fine print.

“Even if the full service turns out to be good, you’d still be limited by the hotspot functionality of the phone—that is, if hotspot is even allowed to be used on direct-to-cell,” Gwinnell says. “I could see there being additional limitations because of satellite availability.”

Priority and availability will be entirely up to the satellite provider, he points out. And no one’s really explained how roaming, throttling, or data priority will be handled yet. That would matter a lot when you’re relying on it for work or in any sort of crisis.

Current Solutions

While satellite direct-to-cell technology continues to evolve, there’s no need to sit around with zero bars. TravlFi already offers reliable connectivity solutions that help nomads, RVers, and off-grid explorers stay online in the here and now. Our lineup of portable hotspots and multi-carrier SIM cards are designed to work across major networks, intelligently (and automatically) switching between carriers to keep you connected wherever your road trip takes you.

Whether you're streaming a show in your camper, sending a work email from a trailhead, or uploading content from a remote boondocking site, TravlFi’s current tools are built to handle the job. Devices like the TravlFi Journey Go Hotspot and TravlFi XTR Pro Router provide flexible, plug-and-play options that prioritize convenience without sacrificing speed or coverage.

We’re as excited as you about the future of connectivity, but we also want you to know: You don’t have to wait to experience reliable internet on the road. TravlFi’s solutions are designed with digital nomads in mind—offering coverage, control, and customization right now.

And when direct-to-cell does become mainstream? You’ll already be part of a community that’s been leading the charge.

In the meantime, our customer support team is always available to help you find the best plan or device for your lifestyle. We’re not just watching the future unfold—we’re building toward it while keeping you connected every step of the way.

The Road Ahead

The path to seamless global connectivity is fraught with challenges, but the momentum is undeniable.

As satellite networks grow in density and capability, voice and data services will become technically feasible (we’ve already seen proof of success with AT&T and AST SpaceMobile). But regulatory bodies like the FCC will need to approve expanded services, and providers must balance expansion with responsible management of the space environment.

The vision is a seamless hybrid network where terrestrial and satellite coverage work together, wherein consumers don’t even realize when their device switches from ground-based towers to satellites—they’ll simply enjoy coverage wherever they are.

“I expect to see every competitor jump into this space,” he says, “and I see wireless-satellite becoming a new slice of the pie.”

But it’s going to take a long time to get there—five, 10, 20 years or more, according to Kagan.

The Bottom Line

Direct-to-cell satellite connectivity is here, and it will expand rapidly.

“The wireless industry has been with us for 50 years. It has grown and changed over time from analog to digital, and from 2G to 5G today,” says Jeff Kagan, wireless industry analyst. “Wireless continues on its march forward with satellite services. What we have today is much more robust than what we saw Apple start with.”

Rather than just serving as an emergency locator beacon, Kagan says, cellular satellite service today acts more like a broadband connection, letting the user do much more. “These are truly imaginative and necessary services,” he says.

Still, according to Kagan, the current weaknesses of such technology “will have to be strengthened before wide groups of customers will jump in.”

More Like This:

- Is RV WiFi Any Good? RV-ing Experts Dish Out the Truth

- An RV Internet Expert Shares Tips for Optimal RV WiFi Setup

Article By: Amanda Capritto

Amanda Capritto is a fitness and outdoors journalist who travels full-time in a Winnebago camper van. Her work has appeared in national and global outlets like Lonely Planet, Reader's Digest, CleverHiker, CNET, and more.